US government may be abandoning the global climate fight, but new leaders are filling the void – including China

When President Donald Trump announced in early 2025 that he was withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement for the second time, it triggered fears that the move would undermine global efforts to slow climate change and diminish America’s global influence.

A big question hung in the air: Who would step into the leadership vacuum?

I study the dynamics of global environmental politics, including through the United Nations climate negotiations. While it’s still too early to fully assess the long-term impact of the United States’ political shift when it comes to global cooperation on climate change, there are signs that a new set of leaders is rising to the occasion.

World responds to another US withdrawal

The U.S. first committed to the Paris Agreement in a joint announcement by President Barack Obama and China’s Xi Jinping in 2015. At the time, the U.S. agreed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025 and pledged financial support to help developing countries adapt to climate risks and embrace renewable energy.

Some people praised the U.S. engagement, while others criticized the original commitment as too weak. Since then, the U.S. has cut emissions by 17.2% below 2005 levels – missing the goal, in part because its efforts have been stymied along the way.

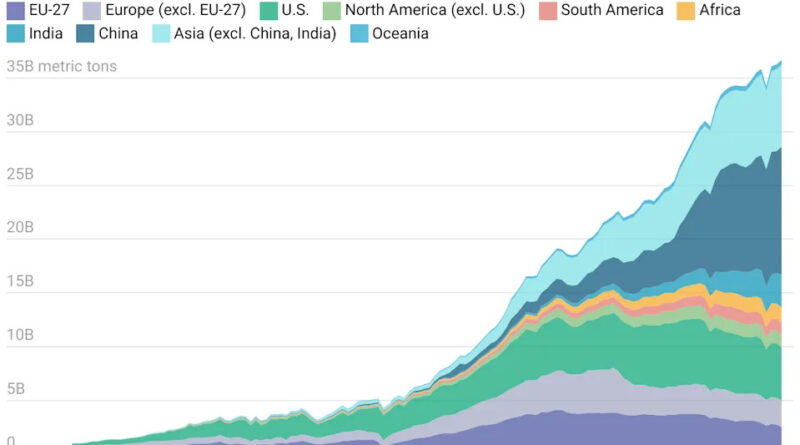

Just two years after the landmark Paris Agreement, Trump stood in the Rose Garden in 2017 and announced he was withdrawing the U.S. from the treaty, citing concerns that jobs would be lost, that meeting the goals would be an economic burden, and that it wouldn’t be fair because China, the world’s largest emitter today, wasn’t projected to start reducing its emissions for several years.

Scientists and some politicians and business leaders were quick to criticize the decision, calling it “shortsighted” and “reckless.” Some feared that the Paris Agreement, signed by almost every country, would fall apart.

But it did not.

In the United States, businesses such as Apple, Google, Microsoft and Tesla made their own pledges to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Hawaii passed legislation to become the first state to align with the agreement. A coalition of U.S. cities and states banded together to form the United States Climate Alliance to keep working to slow climate change.

Globally, leaders from Italy, Germany and France rebutted Trump’s assertion that the Paris Agreement could be renegotiated. Others from Japan, Canada, Australia and New Zealand doubled down on their own support of the global climate accord. In 2020, President Joe Biden brought the U.S. back into the agreement.

Now, with Trump pulling the U.S. out again – and taking steps to eliminate U.S. climate policies, boost fossil fuels and slow the growth of clean energy at home – other countries are stepping up.

On July 24, 2025, China and the European Union issued a joint statement vowing to strengthen their climate targets and meet them. They alluded to the U.S., referring to “the fluid and turbulent international situation today” in saying that “the major economies … must step up efforts to address climate change.”

In some respects, this is a strength of the Paris Agreement – it is a legally nonbinding agreement based on what each country decides to commit to. Its flexibility keeps it alive, as the withdrawal of a single member does not trigger immediate sanctions, nor does it render the actions of others obsolete.

The agreement survived the first U.S. withdrawal, and so far, all signs point to it surviving the second one.

Who’s filling the leadership vacuum

From what I’ve seen in international climate meetings and my team’s research, it appears that most countries are moving forward.

One bloc emerging as a powerful voice in negotiations is the Like-Minded Group of Developing Countries – a group of low- and middle-income countries that includes China, India, Bolivia and Venezuela. Driven by economic development concerns, these countries are pressuring the developed world to meet its commitments to both cut emissions and provide financial aid to poorer countries.

China, motivated by economic and political factors, seems to be happily filling the climate power vacuum created by the U.S. exit.

In 2017, China voiced disappointment over the first U.S. withdrawal. It maintained its climate commitments and pledged to contribute more in climate finance to other developing countries than the U.S. had committed to – US$3.1 billion compared with $3 billion.

This time around, China is using leadership on climate change in ways that fit its broader strategy of gaining influence and economic power by supporting economic growth and cooperation in developing countries. Through its Belt and Road Initiative, China has scaled up renewable energy exports and development in other countries, such as investing in solar power in Egypt and wind energy development in Ethiopia.

While China is still the world’s largest coal consumer, it has aggressively pursued investments in renewable energy at home, including solar, wind and electrification. In 2024, about half the renewable energy capacity built worldwide was in China.

While it missed the deadline to submit its climate pledge due this year, China has a goal of peaking its emissions before 2030 and then dropping to net-zero emissions by 2060. It is continuing major investments in renewable energy, both for its own use and for export. The U.S. government, in contrast, is cutting its support for wind and solar power. China also just expanded its carbon market to encourage emissions cuts in the cement, steel and aluminum sectors.

The British government has also ratcheted up its climate commitments as it seeks to become a clean energy superpower. In 2025, it pledged to cut emissions 77% by 2035 compared with 1990 levels. Its new pledge is also more transparent and specific than in the past, with details on how specific sectors, such as power, transportation, construction and agriculture, will cut emissions. And it contains stronger commitments to provide funding to help developing countries grow more sustainably.

In terms of corporate leadership, while many American businesses are being quieter about their efforts, in order to avoid sparking the ire of the Trump administration, most appear to be continuing on a green path – despite the lack of federal support and diminished rules.

USA Today and Statista’s “America’s Climate Leader List” includes about 500 large companies that have reduced their carbon intensity – carbon emissions divided by revenue – by 3% from the previous year. The data shows that the list is growing, up from about 400 in 2023.

What to watch at the 2025 climate talks

The Paris Agreement isn’t going anywhere. Given the agreement’s design, with each country voluntarily setting its own goals, the U.S. never had the power to drive it into obsolescence.

The question is if developed and developing country leaders alike can navigate two pressing needs – economic growth and ecological sustainability – without compromising their leadership on climate change.

This year’s U.N. climate conference in Brazil, COP30, will show how countries intend to move forward and, importantly, who will lead the way.

Research assistant Emerson Damiano, a recent graduate in environmental studies at USC, contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Shannon Gibson, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Read more:

Shannon Gibson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.